Shape of a Ship’s Hullform

Article

The ship’s hull has evolved into a suprisingly subtle shape to meet following requirements which are often in conflict with each other:

- A good carrying capacity for the overall size of the vessel.

- Good sea-keeping qualities.

- The ability to be easily driven thorugh the water.

- The possession of the ability to remain basically upright in seaway

- The strength to withstand the stresses and strains due to the motions of the sea

Underwater hullform and coefficients

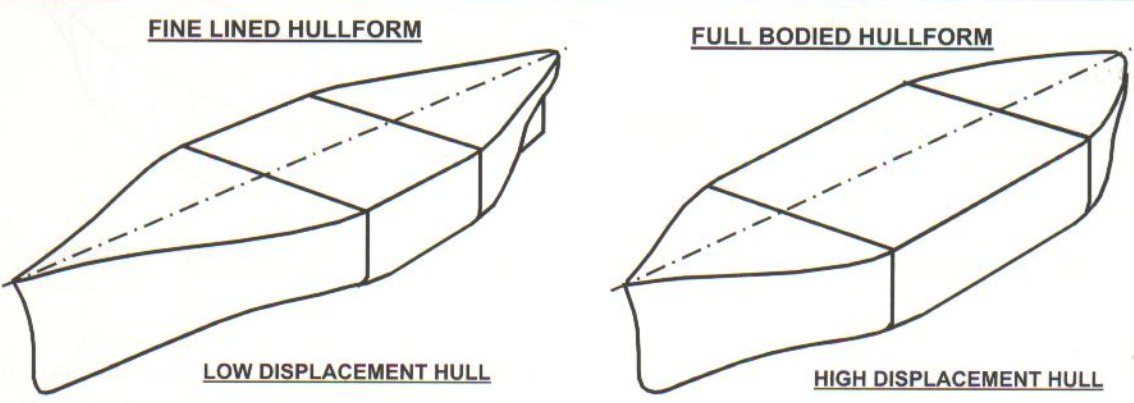

For any ship operating in open water, carrying capacity must be traded off, to some extent, againts seakepping performance. Such hull can be considered as three seprate sections merging into each oter along the ship’s length. The forward and aft sections are finely tapered towards the bow and stern where as the midship parallel body section is box shaped. The proportion of this centre region to the total underwater lenghth varies from one design to another. Ships with fine lines have relatively short length of parallel body where as bluff, of full formed, hulls may be box shaped for over half of their length.

The fine lined hull is more easily driven through the water than the full bodied form but it has a reduced carrying capacity. The hull form also affects other seakeeping qualities, such as the vessel’s rolling and pitching characteristics.

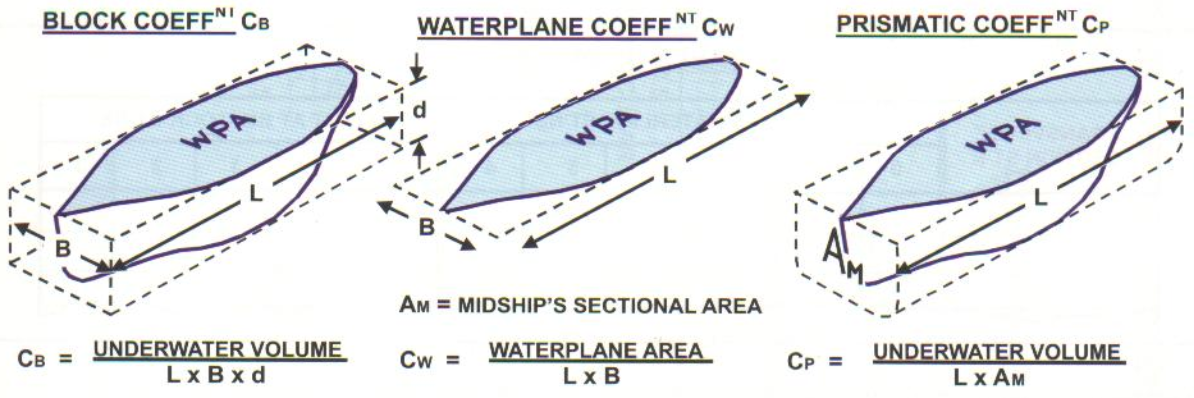

The degree of hull fineness can be expressed in terms of measured ratios, known as hul coefficients. These coefficients compare the actual immersed hull shape to the rectangular of the same overall dimenions. The three most commonly used coeffcients afe follows:

The Lines Plan

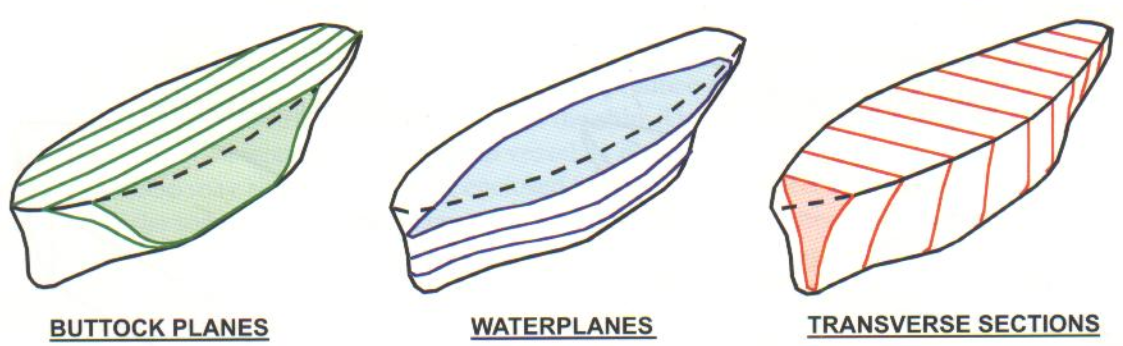

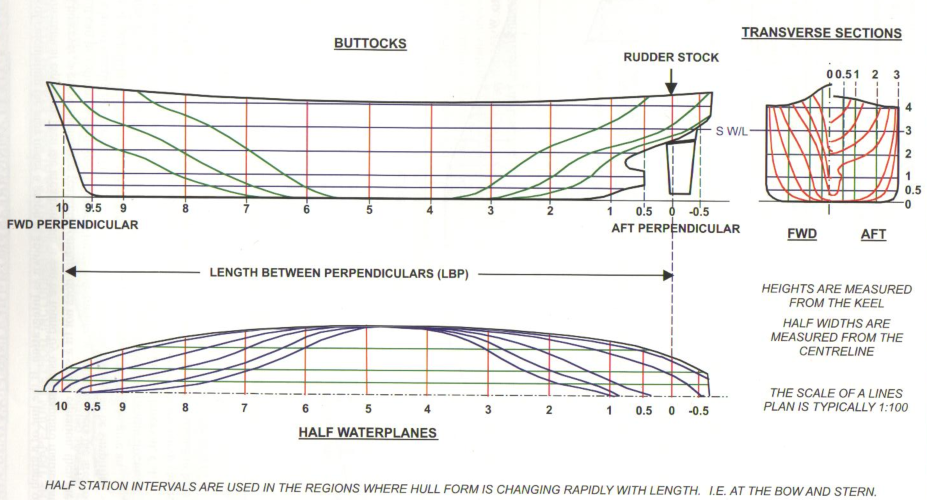

The forst stage of building a ship’s is the drawing out of scale plans which accurately defines its three demensional shape on a flat piece of paper. The standard technical drawing approach of three mutually perpendicular views is used to produce plan, side and end elevations but the method is modified to show the changing curvature of the hull in all three dimensions. This is achieved by illustrating slices of the hull at regular intervals in each dimension, as shown below:

- Buttockplanes : These are vertical fore and aft sloces taken atreguler beam intervals

- Waterplanes : These are horizontal fore and aft slices taken at reguler draft intervals.

- Transverse Section : These are vertical athwartships slicec taken at reguler length intervals.